The Power Stones of the Owambo Kingdoms

Omililo dhomamanya Giilongo yAawambo

Ondonga Power Stone

One of the possibilities that arises from the Africa Accessioned project is that objects that have particular sacred significance to a community might be located in an overseas collection. The the Finnish Government and museum sector have shown sensitivity to the goodwill that can be generated by the repatriation of objects of importance. Since its independence in 1990 two important artifacts have been returned to Namibia. The `Power Stone’ (Emanya lomundilo woshilongo) of the Kingdom of Oukwanyama was returned to the Kwanyama Traditional Authority in 1990 and in 2014 the stone that was part of the regal symbols (omiya dhoshilongo) of Ombalantu was returned to the Mbalantu Traditional Authority (Ashipala, 2014). The stones were sacred objects and it was believe that if they were removed from the kingdom or damaged serious misfortune would strike the kingdom (Eirola1992: 49)

When Namibia hosted the Conference of the International Committee of Museums of Ethnography (ICME) in 2012, MAN was able to arrange for Ms Raili Huopainen (Director of the Kumbukumbu Museum of the Finnish Evangelical Lutheran Mission (FELM) and Ethnographic Museum of the University of Zurich in Switzerland to visit Nakambale Museum. One of the positive outcomes of that meeting was that Ms Huopainen informed us that her museum would be closing shortly, but that, before it closed, she would ensure that all the Namibian objects in the collection were photographed and we obtained a complete folder of digital images of the FELM collection when we visited Helsinki in 2015 as part of the Africa Accessioned project.

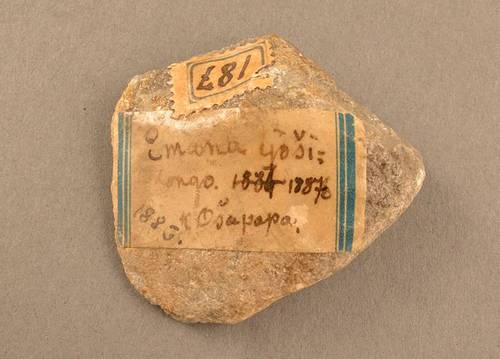

The folder contains a mixture of images that includes some that are clearly from FELM’s other mission fields, such as China, and so the photograph archive still needs to be edited and linked to a translation of the FELM catalogue (which is not yet available as a soft copy). Three of the photographs were of particular interest as, we presumed, they were images of the stones from Oukwanyama and Ombalantu that had been previously been returned to Namibia. I contacted Ms Lahdentausta to request a translation of the catalogue information about the two objects (catalogue numbers 5620 and 8240. When we received the reply it was clear that these were new objects. We believe, strongly that the first object is a piece of the sacred stone of Ondonga. The catalogue entry reads:

Artifact 5620: “Piece of Ondonga sacred stone, Oshipapa. The piece is from a meteorite fallen on the Earth in 1883 or 1886. Power stones are believed to symbolize good government, stability and connection with the forefathers’ spirits”.

We believe that the entry relates exactly to the description of an incident that is described very clearly in Matti Peltola’s biography of Martti Rautanen, which Peltola based on his translation of the account found in Rautanen’s own diary

“In February 1886, the desire for knowledge gave Rautanen and Dr Schinz a life-threatening experience. It concerns a stone, which Rautanen calls `Oshilongo-Sten’ `the stone of the kingdom’. Stones are rare in Ovamboland, so rare that religious reverence was shown to them. In many cases they probably were meteorites, which partly explains the awe. No mention of them was publicly made, especially when strangers were present.

Unidentified Power Stone

Martin Rautanen and Dr Schinz had taken a trip to the site of late King Nembungu’s court, which was to the east of Olukonda, a few hour’s journey in an ox-wagon. Their attention was drawn to an enclosure. When they asked what it was, they were told that there were amulets there used in making rain and it was forbidden to examine them. Rautanen knew that there was a stone inside such an enclosure, but he had also heard of a special stone which was near there. Nambahu, one of the young men from the mission station, said that he knew where it was. He guided Rautanen and Dr Schinz to the place. Part of the stone was visible. Its even surface a few decimetres in extent, rose slightly from the ground. Dr Schinz was in a way disappointed, because the stone was evidently not meteorite, but quartzite. In order to be able to study It closer, he and Rautanen both cut pieces for themselves and then covered the sides of the stone with sand, as they had been before.

Before they returned, Rautanen’s attention was drawn to a heap of wood which nobody had taken home, though fire wood was scarce. They were wooden posts used for building a stockade. Rautanen studied the place and found out that there had been a house. They were standing on the site of the court of King Nembungu, a circumcised King who had ruled Ondonga a generation before, perhaps in the 1830s, and had been held in high regard. Then they returned to Olukonda (115-116)

Grave of Omukwaniilwa Nembungu lya Mutundu

A local Ndonga historian, Hans Namuhuja, argued that Omukwaniilwa Nembungu lyaAmatundu was the ruler of Ondonga in the period 1750-1810. Namuhuja also states that Omukwaniilwa Nembungu is remembered as the custodian of iidhila (taboos) and omisindila (rites). The grave site at Oshamba (Iinenge) is one of the most significant heritage sites in northern Namibia (Namahuja, 1996: 11; Silvester & Akawa, 2010: 69). Lovisa Nampala refers to an interview she conducted with Shilongo Uukule on 17th August, 2001 in which it was stated that during the reign of Omukwaniilwa Nembungu a meteorite landed near his capital, Iinenge, and it was adopted as the stone of the kingdom (omulilo gwemanya lyoshilongo). The stone was associated with the art of rain-making. After Nembungu’s death people would still visit Iinenge for rain-making and, if this was unsuccessful, travel further north to the Kingdom of Evale, which was the place where the most powerful rain-makers were found (Nampala, 2006, 55)

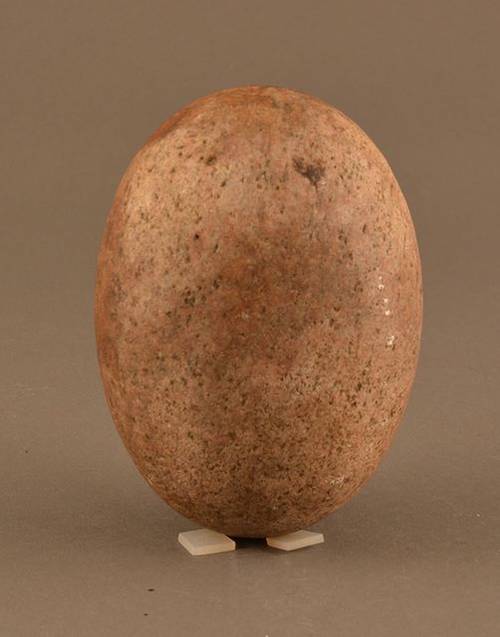

The second stone was described in the translation from the FELM catalogue as:

Number 8248: “Ritual stone from Angola or Namibia, a ‘rain stone’, may be a kind of stone with the help of which rain could be aroused or engendered”.

The provenance of this stone is, thus, unclear (`Angola or Namibia’). One possibility is that it might be the actual stone from Evale. Tatekulu Helao Shityuwete, whose father, Neliudi Shityuwete, was a member of the royal family at Evale described having seen the stone in the 1930s at a time when Christianisation meant that king was losing faith in his rain-making powers (information given at a presentation at the Namibia Scientific Society, 24th November, 2014). Mr Shityuwete left Evale (which is now in Angola) at an early age (5 or 6) and so it is doubtful whether he would be able to make an absolutely positive identification although there may be others who could (Shityuwete, 1990: 1-2). If the stone was from Evale, it would also be necessary to find out where the stone was originally located and explain the way in which it might have ended up in Finland. The fact that the border with Angola was only finally agreed in 1929 might mean that there was easier access to the kingdom in the early twentieth century and it was common for people to move within the region as the border was only enforced more effectively after the death of the Kwanyama Ohamba Mandume yaNdemufayo in 1917.

Whilst Evale was the most powerful rain-making kingdom on the region, it was widely believed that the ancestors of dead kings (ovakwamhungu) were the holders of the rain (Tonjes, 1996: 16; Williams, 1991: 109, 168). It is clear that a number of the Ovambo Kingdoms (perhaps all) held sacred stones and that rain-making was associated with stones that were located at the graves of ancestral, circumcised, kings. Edwin Loeb, for example, states that rain-making is described in OshiNdonga as okusagela kuomvula imenge (to make rain in the grove of the king’s grave). “It is said that in Ondonga there were four sacred stones (omamainja) near the grave of a king and that people still go to them to make sacrifices to the spirits that bring rain. Major Hahn [`Shongola’, the `Native Commissioner for Ovamboland’, 1920-1945, JS) informed me that with some natives he sought for these stones but found only one small one; the others, he was told, are underground” (Loeb, 1962: 277). The historian Jason Amakutuwa stated that the Uukwambi Kingdom also had two big round stones – “They called these stones `rain eggs’ or `rain thunderbolts, the eggs of Nuutoni’”. According to the late Jason Amakutuwa, the stones were kept at Iino (Salokoski, 2006: 229, Ndalikokule, 2010: 7). The description seems to fit object 8248 and the fact that the museum does not seem to have information about the origin of the stone suggests that it might be difficult to identify conclusively.

The Power Stones are an example of the way in which museum catalogues reflect the motives for collection and will always only provide a partial biography of an object. The importance of linking an object to the place and the intangible heritage associated with it is evident. An open dialogue can provide the opportunity to build greater understanding of the historical relationship between Namibia and Finland. Such dialogue can provide a platform for meaningful cultural exchange that moves beyond the static display of difference.